Church bells among crow song

This week much of the country fell silent for a while and that stillness was the occasion for a chance encounter and finding within the silence the music of bells among crow song. Join us aboard the Erica tonight as we are touched by the enigmatic qualities of bells and stillness.

Journal entry:

21st September, Wednesday

Dew, the smell of sheep and wet grass.

Rooks jostle the lightening sky.

The company of ducks hunched at the water’s edge

Shake themselves awake

And drop into the pool of water

The colour of dawn.

Episode Information:

All field recordings made on 19.09.2022 and features the bells of St Peter's church, Wootton Wawen.

You can find out more about the bells in this recording by going to: The Church Bells of Warwickshire and the church they are housed in at: Saxon Sanctuary.

In this episode I read short extracts from:

SeánStreet’s (2012) The Poetry of Radio: The colour of sound published by Routledge.

Seán Street’s (2019) The Sound inside the Silence: Travels in the Sonic Imagination published by Springer.

I also read two short excerpts from John Betjeman.

John Betjeman (1958) Introduction to English Country Churches that can be found in The Best of Betjeman (selected by John Guest) published in 1978 by Penguin

John Betjeman (1960) Summoned by Bells originally published by John Murray.

I also make a very brief mention of Dorothy L Sayer's (1934) detective story Nine Tailors, currently being published by Hodder and Stoughton.

Steve Tyrell’s vlog recording his adventures on the NB Precious Jet can be viewed here: Narrowboat Precious Jet.

David Keating’s Instagram account to view his photographs: david_keating.

For more information about Nighttime on Still Waters

You can find more information and photographs about the podcasts and life aboard the Erica on our website at noswpod.com. It will also allow you to become more a part of the podcast and you can leave comments, offer suggestions, and reviews. You can even, if you want, leave me a voice mail by clicking on the microphone icon.

General Details

In the intro and the outro, Saint-Saen's The Swan is performed by Karr and Bernstein (1961) and available on CC at archive.org.

Two-stroke narrowboat engine recorded by 'James2nd' on the River Weaver, Cheshire. Uploaded to Freesound.org on 23rd June 2018. Creative Commons Licence.

Piano and keyboard interludes composed and performed by Helen Ingram.

All other audio recorded on site.

Contact

For pictures of Erica and images related to the podcasts or to contact me, follow me on:

- Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/noswpod

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nighttimeonstillwaters/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/NoswPod

I would love to hear from you. You can email me at nighttimeonstillwaters@gmail.com or drop me a line by going to the nowspod website and using either the contact form or, if you prefer, record your message using the voicemail facility by clicking on the microphone icon.

JOURNAL ENTRY

21st September, Wednesday

Dew, the smell of sheep and wet grass.

Rooks jostle the lightening sky.

The company of ducks hunched at the water’s edge

Shake themselves awake

And drop into the pool of water

The colour of dawn.

[MUSIC]

WELCOME

The skies are dark. The silvered sliver of the old harvest moon has dipped below the horizon. The sky awaits in silence for a new moon about to rise. A northerly wind blows chill across the waters. The ducks are huddled in their noisy sleep along the bankside and its warm here inside

This is the narrowboat Erica narrowcasting to you on this September night. Thank you for coming. I am so glad you managed to make it. The stove is lit and the coals glow cherry, the kettle has boiled, your special mug is here waiting for you. Let’s duck down inside and make ourselves comfortable.

[MUSIC]

NEWS FROM THE MOORINGS

It feels as if I have been away for a really long time! It’s so nice to be back here with you again, sitting at this desk, in the darkness, lit by this little pool of light, that glints on the dark waters outside the cabin window, with my microphone in front of me and all the world to talk to.

A special hello to all the ham radio operators. A number have been recently contacting me after having found this podcast. I can see so clearly the overlap between what you do and what I am trying to do.

Also a very special hello and sleep tight to Rory. Your dad showed me a picture of you tucked up in bed and dropping off to sleep to this podcast. I am glad you are enjoying it, sleep well and pleasant dreams.

The weeks are sliding by as are the seasons. There’s still the pull between summer and autumn that you always get, but the equinox has passed and in the old northern cultures, night is gaining strength over the day – darkness is now just a little longer than the daylight. The dusks are also deepening with the sun dipping much lower below the horizon to bring true night-time.

The hedgerows are sprinkled with red berry candles and are being touched by the flame of autumn russets and browns and golds. Like the crow families, the ducks are gathering in larger groups, swimming in little gangs that hector and debate their place in the world and on this small part of the cut. But the carp are still dozing in the sunny shallows by the bankside and the afternoon air hums with insects.

And the cygnets are continuing to grow. They are now getting so independent. I spotted them a couple of days ago, slowly swimming, with the casual one footed paddle-stroke, down the dead centre of the canal. I could hear them before I could see them. The soft peep, peep, calls. There was no sign of their parents, but they seemed to be quite content. The cheeps were not location calls, trying to find their parents, they were too quiet for that. They seemed more like the vocal equivalent of holding hands. For a while, I walked with them, along the towpath. Stopping every now and then to forage or explore an overhanging branch laden with blackberries, or rifle through a thick clump of rushes or yellow iris leaves. It was not for several hours until their parents arrived. I was getting a little anxious fearing that something had happened to them. A family reunited without fanfare, without fuss.

We had a wonderful time with dad and thank you to everyone who sent their greetings or well wishes. It was lovely to be together again. Dad insisted on doing all the locks and taking his turn at the tiller, despite being 93! I said 94 on Twitter – sorry, I prematurely aged you Dad! Dad’s not 94 until December! We got absolutely soaked twice.

But it has been a strange and complicated few weeks hasn’t it? It’s not been easy. Yesterday we found out that one of our neighbouring boaters had died. It was unexpected and a shock. We don’t know the details, but it seems as if life had become too much for him. Death raises complicated emotions anyway, these types even more so. It’s hard to process. The mind gets into cycles, replaying last moments, last movements, last conversations. Shock, disbelief, anger even, but also feelings of guilt, of somehow drawn in and complicit. Life goes on here, but it is a bit quieter, subdued. ‘Are you okay?’ takes on greater meaning.

So do the flights of wild geese, chevroning the towering skies.

[MUSIC]

CABIN CHAT

[MUSIC]

BELLS AMONG CROW SONG

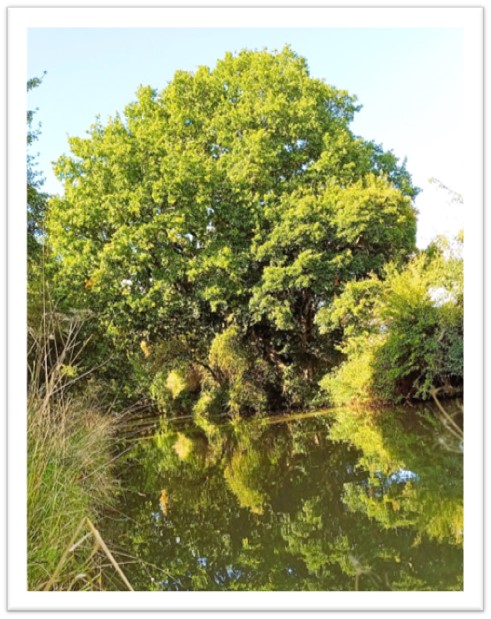

Watery green light, leafy and fern green, diffused by this short corridor of wood, through which the canal cuts with its own green dark waters.

Deep silence.

But, of course, it is not silent. It is nothing like silence. I suppose I could try deep stillness instead. But that too would be wrong for it is far from still. There is a constant busyness of tiny movements, Peaceful then? Yes, but somehow, it still isn’t quite right. Yes, it is peaceful here. There is a sense of tranquillity standing beneath the spread of ash and oak leaves that almost – just almost – makes a hollow-way of the canal. But peaceful speaks to the wrong things.

It is not peace that descends and wraps me in an embrace that makes my mind still and heart race. And so, I keep coming back to ‘silence’.

Listen –

This is the silence that does not speak of the absence of noise. A living silence can never be noiseless. It’s why polar explorers, on the rare windless days, thought they would go mad at the dead, soundless, silence. Their minds conjuring phantom voices to fill the void, even though they froze the heart.

Yes, I think I was right the first time. Deep silence, that you can stretch your ears to the furthest reaches of the sonic horizon and all you can hear – apart from a sporadic car in the distance – is the uncluttered earth.

And this silence – that is so tangible to me that I can almost plunge my hand into it and let it run silky through my fingers – is nothing to do with the landscape that I find myself in. This is the type of silence you can feel with your eyes in a Hopper painting. And it is a silence that descends upon me from above, internally. And I realise, it is not the world that is silent – I am standing here trying to record it, after all! – it is me that is silent. And I realise that I have pined for this for such a long, long time, this silence in a parched desert of unceasing noise without realising it.

In most parts of Britain, we can rarely acoustically encounter our landscapes without the sonic ripping of machinery. When the pandemic hit, it is one of the things that made that first lock-down so striking. Each morning and evening of that warm sunny Spring of 2020 greeted us with such rich deep soundscapes – alive with song and movement. For the first time, we could let our ears stretch their cramped legs; letting them roam free to explore the rolling sonic fields and downs. It was like taking a long deep breath or drinking deeply from a fountain. Distant sounds that had been lost to us, smothered under the dead-weight of the smog of the noise of modern life, stretched out to the far distant.

I heard a cuckoo for the first time for years. Far off, clear, distinct, in a wooded copse, apple green and sunny. Farm dogs barking over Winderton way. The soft, golden tolling of the hours from a distant village clock. The sound of children playing in a garden.

It is not surprising that so many people rediscovered the world outside their doors that Spring, when that world can sing more sweeter than any rock-bound siren. Who could resist such a hymning welcome drawing us into its heart and saying this is where you belong?

Today. Today is a little like that. The world – or at least Britain, for the most part, has stopped. The funeral of a Queen, the passing of an age, an age that most have known has long since passed. We have lost so much over these past few decades. And now all the roads are nearly empty. The airways above are not so busy, and a wash of birdsong and life unhindered tumbles and flows down the valleys, across the fields, stretching over the hillsides and woods. And I am again captured in this un-silent silence.

In the pause we have made, the world has come alive again with sound.

And then I hear it – or to be more accurate, I become aware of it, sensing it on the very edge of my hearing – among the starling and thrush, the finch chitter and pigeon, and the crow song, the haunting slow toll of a muffled bell.

There is something so profoundly beautiful and right about the sound of a bell – muffled in grief – softened by distance that rings out into the sky full of song. It calls to something deep within us – as this whole thing has.

“Who has heard a muffled peal and remained unmoved?” John Betjeman writes, and who indeed?

[READING]

I try to record it, but I know it is hopelessly far away. I am sensing it rather than hearing it. It eddies and drifts on the light wind. Lifting with the circling rooks at play.

For a while the towpath is empty of all human life but me. Late summer insects buzz around the seedheads and the longsword blades of flag and I bathe in this ocean of sound that fills me with such silence.

Then a figure appears, rounding the corner where the bank is knotted with tree roots and animal dens. He stops and then starts and then stops again. He disappears up the steep bank, seeming to rootle through the roots, and then slithers back down to the towpath. In this fashion, he makes his slow way haphazardly towards me. I stop recording. A shortish, wiry, man, slightly bowed of leg, perhaps in his 60s, perhaps a bit older, but I am hopeless with ages and people no longer look old to me now. He has the look of a stock character in a film, a whiskery, grey-white, cloud of an RAF moustache bristles on a face loved and carved by many winter’s suns. His eyes are still young and burn with life. Half gnome, half retired colonel.

“I suppose you are not going to tell me you are a muggle are you?” I am slightly surprised that his voice betrays neither Oxbridge or the Sandhurst mess halls.

I have to confess that no, I wasn’t, and that that the thought of offering such a greeting had not even remotely crossed my mind. We stop and stare at the towpath and our feet for a while. If this was a myth, a portal would open in the bank and a pure white stag chased by hunting hounds would bound passed. He would then say something too wise for words to hold and I would be forever changed. But this isn’t a mythic tale, there is no sceptred stone that glows with light from within, just a world pausing in sadness for a loss that is far greater than the loss of one human, but something deeper, more intangible.

And so, I break this beautiful un-silent void with a cataract of words, as I always do. Lingiusts call it ‘phatic communication.’ The creation of noise for socio-pragmatic relational functions than denotational conveyance of information. But I have long since stopped listening to the gush of language I seem incapable of quenching. Words about ‘deep-soundscapes’, lock-down, recording, acoustic washes of the natural world devoid of cars and aeroplanes and bansheeing saws and engines. I hate it. I would much rather that we’d just stand for a while a listen to the branches thrash with pigeons and the jackdaws spit their gobbets of laughter down onto the silent green canal water. But his eyes light up and so does his face as it creases into the easy folds of his smile. Perhaps I am the wizard in this legend’s tale. Perhaps I should be the one saying wise things and that his life would be, henceforth, forever changed? But I can’t think of anything wise.

He then tells me how he is seeking a hidden box. He thought it was on the corner, where I first saw him, the corner where there is a rabbit trail through the undergrowth and I once saw a kingfisher alight. And then he decided that it must be where I was standing. We both look at the towpath, both knowing it won’t be there. He consults the screen of his phone again, jabbing it with a finger that is pleasingly engrained with soil and good-use. No, it’s still 20 metres further on. I look to where he points. It is opposite to the shallows where the heron likes to fish.

He says he will try to be as silent as possible. I say ‘good luck’ with your hunt.

And so, we part. Two non-wizards, each on the threshold of finding what they seek, pacing out the paths of their own mythic worlds. One sounds, the other a little hidden box tucked in the undergrowth amongst the roots of a tree that is overlooked by a heron’s gaze.

A little later I look back and see him happily scuttling in the undergrowth. A human squirrel. The heron has gone.

Then the six bells of St Peter’s nestled in the valley below begin to ring out. One of them has been ringing out across the village rooftops, rolling down the streets and over the folds of fields and forest since 1591. That is before the conflagrations of the last century, before the industrialisation, before the fencing of the land, before the Great Plague, before the Civil War, before the monarchy was disinvested of their divine right to reign. The first Queen Elizabeth was still on the throne – and this same bell would one day peel out the news of her death too. Shakespeare had left for London, but was yet to write a play – at least, one that survives. This is a bell that has the full measure of time, that takes the long road. These chimes have rung in so many ears – human and non-human. Outliving even the trees. And now, in 2022 on the death of another Queen Elizabeth, it lends its song with those cast much later. The great tenor of 1719, the A# of 1784, the Bb cast in Gloucester in 1803, and the two young siblings cast and hung in 1955. Here is a consistency you can trust the mellow, golden thunder of music that has, overtime, carved itself into the landscape. Old bells. As old as crow song.

Years ago, I heard an audiobook of Dorothy L Sayers’s Nine Tailors. The nine tailors refer to the bells of parish church featured in the story. Each chapter begins with the notation used to call changes – or ring the bells in intricate and seemingly arcane ways. A calligraphy of numbers in metrical columns – numbers flow and weave across the page. A code-stream of unlocked sound. The esoteric language of change ringing calls.

[READING]

Perhaps it is this rather arcane, anachronistic nature, that fills a particular need at the moment. A sense of consistency, permanency in a fast-flowing world. That, whatever happens, there will as Rupert Brooke so memorably expressed it that when “Stands the Church clock at ten to three?” There will be “honey still for tea?” Or finding that ‘still point in a turning world’ to quote Eliot.

I remember dad asking me many years ago, why is everyone looking backwards? In the 90s the nostalgia business was booming. When he was young it was all about the future. I remember that too – the 60s and early 70s – the optimism of the future. Where has that gone, he asked? Today, even in our politics it is about looking back to the past, trying to recapture something that was never really there.

But there is something comforting about hearing these old bells toll out – their mysterious arrhythmic songs (though campanologists would rightly take exception to that description) following those arcane diagrams and tower captain’s esoteric change calls.

But it is even more than that – more than a comforting tradition to ease us through the anxieties of change.

What is it about bells that resonates – literally!- so deeply? They seem to be able to express for us those things we find ineffable; beyond words. It is not surprising they are used by so many faiths.

In his wonderful study of sound and radio, The Poetry of Radio: The colour of Sound, one of my core textbooks for this podcast, Sean Street cites from an interview he had with composer John Harvey in which Harvey says...

[READING]

There is something so powerful about this quality of bells as cicerone ushering the listener to a place of silence.

In the context of the book, it is this relationship between noise, silence and the radio listener that Sean Street explores so beautifully, calling the listener, more than that, leading the listener to bring to this experience something of themselves. Filling that void. The fear of ‘dead air’ gives way to an imaginative space of co-creation.

Just as you bring to my recording of bells among crow song on a grey day of national silence your own sets of images and feelings.

Sean concludes his book by stating.

[READING]

So powerful is this image and idea, that Street introduces one of his later books – The Sound Inside Silence, with the theme of the bell ringing,

[READING]

This bell-like quality of leading the listener from the auditory world into the more soulful worlds of imagination is, I think, so beautifully expressed in this very short extract from John Betjeman's autobiographical poem Summoned by Bells.

[READING]

And so I stand here, for a while, on this bridge looking into the silent green depths of the canal listening to old music ring and dance across the fields. And it is right for this day. Church bells among crow song calling us to something deep within ourselves.

SIGNING OFF

This is the narrowboat Erica signing off for the night and wishing you a very peaceful, restful, night. Good night.