Living inside the Seasons

This episode was inspired by a sentence in Beth Kempton's Wabi Sabi and explores how calendars can connect us more closely to the world around us. Join us tonight as we explore the year through the eyes of some Japanese poets and celebrate the unfolding of the summer.

Journal entry:

25th June, Tuesday

“First day this summer

Of real heat.

All day, my shirt has stuck

To my back.

This evening

The clover field

Hums with

The work of bees.”

Episode Information:

The fire of purple loosetrife flaring among the greens

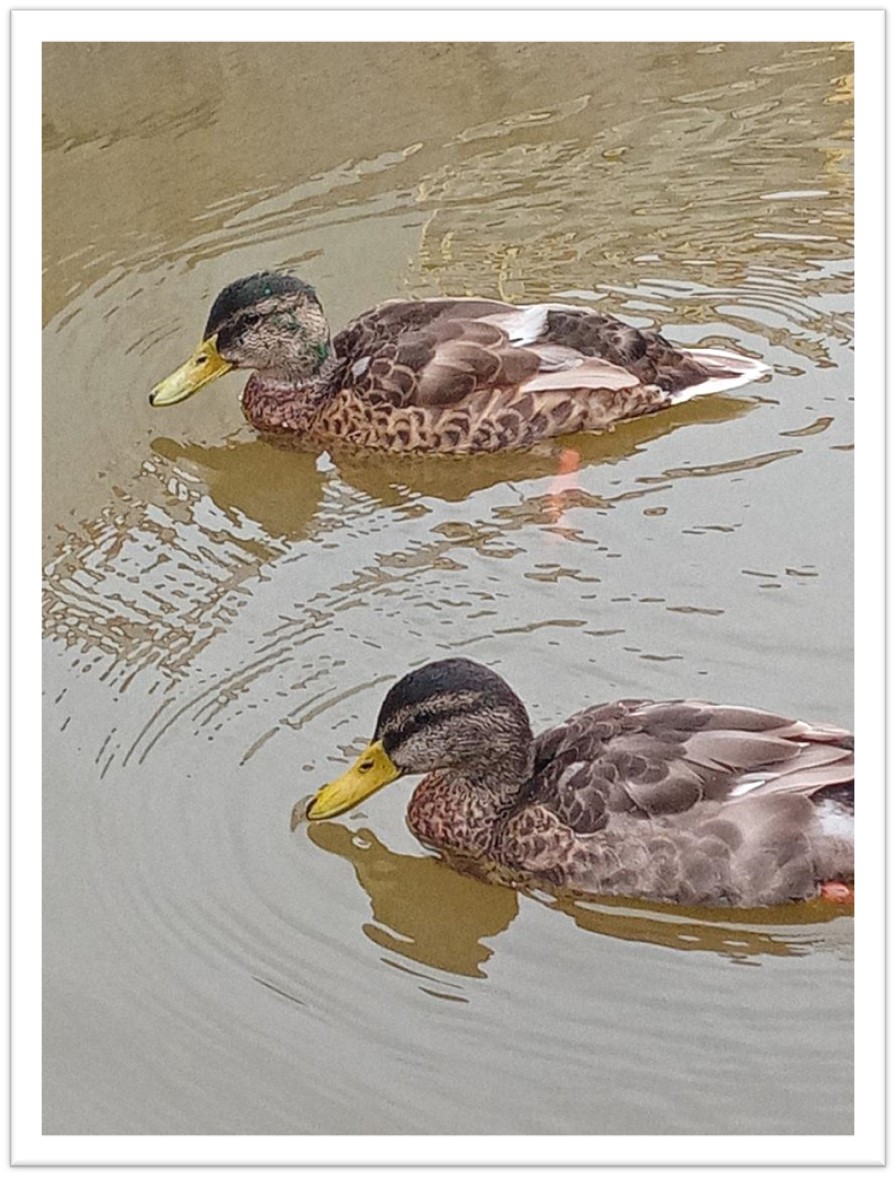

A brace of young mallards

In this episode I recite a number of Larry Hammer’s translations of Japanese poems from the Kokinshū from his (2018) Ice Melts in the Wind published by Cholla Bear Press, as well as haiku from The Four Seasons published (1958) by Peter Pauper Press.

I also refer to Lev Parikian’s (2021) Light Rains Sometimes Fall published by Elliott and Thompson, and Beth Kempton’s (2018) Wabi Sabi published by Piatkus.

With special thanks to our lock-wheelers for supporting this podcast.

David Dirom

Chris and Alan on NB Land of Green Ginger

Captain Arlo

Rebecca Russell

Allison on the narrowboat Mukka

Derek and Pauline Watts

Anna V.

Orange Cookie

Donna Kelly

Mary Keane.

Tony Rutherford.

Arabella Holzapfel.

Rory with MJ and Kayla.

Narrowboat Precious Jet.

Linda Reynolds Burkins.

Richard Noble.

Carol Ferguson.

Tracie Thomas

Mark and Tricia Stowe

Madeleine Smith

General Details

In the intro and the outro, Saint-Saen's The Swan is performed by Karr and Bernstein (1961) and available on CC at archive.org.

Two-stroke narrowboat engine recorded by 'James2nd' on the River Weaver, Cheshire. Uploaded to Freesound.org on 23rd June 2018. Creative Commons Licence.

Piano and keyboard interludes composed and performed by Helen Ingram.

All other audio recorded on site.

Become a 'Lock-Wheeler'

Would you like to support this podcast by becoming a 'lock-wheeler' for Nighttime on Still Waters? Find out more: 'Lock-wheeling' for Nighttime on Still Waters.

Contact

For pictures of Erica and images related to the podcasts or to contact me, follow me on:

- Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/noswpod

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nighttimeonstillwaters/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/NoswPod

- Mastodon: https://mastodon.world/@nosw

I would love to hear from you. You can email me at nighttimeonstillwaters@gmail.com or drop me a line by going to the nowspod website and using either the contact form or, if you prefer, record your message by clicking on the microphone icon.

For more information about Nighttime on Still Waters

You can find more information and photographs about the podcasts and life aboard the Erica on our website at noswpod.com.

00:00 - Introduction

00:45 - Journal entry

01:06 - Welcome to NB Erica

02:11 - News from the moorings

08:39 - Cabin chat

12:52 - Living inside the seasons

14:43 - Lev Parikian's 'Light Rains Sometimes Fall'

20:39 - Exceprt from Lev Parikian's 'Light Rain Sometimes Falls'

24:04 - Poems and haiku from the Kokinshu

31:18 - Signing off

31:34 - Weather Log

JOURNAL ENTRY

25th June, Tuesday

“First day this summer

Of real heat.

All day, my shirt has stuck

To my back.

This evening

The clover field

Hums with

The work of bees.”

[MUSIC]

WELCOME

It's overcast tonight, with heavy walls of clouds - iron grey and old pewter. The last of the twilight casting a platinum wash on their under edges. A breeze is beginning to kick up, so that the alders sigh and rustle. There is the smell of damp in the air, but it is not forecast to rain.

This is the narrowboat Erica narrowcasting into the darkness of a late June night, to you wherever you are.

It's great to see you. I am really pleased you managed to make it tonight. The kettle is singing on the hob, so mind your head on the hatch, come inside and make yourself comfortable. Welcome aboard.

[MUSIC]

NEWS FROM THE MOORINGS

Flaming June has appeared at last. But now, the lick of heat has come and gone, and a soft evening breeze plays over the surface of the water, shimmering an upside-down world of elusive colours. Gnats dance in mesmerising ghostly veils and sheep call from across the canal

Two juvenile drake mallards, swim up. They drift on the almost non-existent current, their orange flippered feet, just visible beneath them, hanging motionless in the darkness of the world of carp, trout and pike. They yawn and slight head bob. From time to time, they make little chuntering chucking noises – talking to me, each other, or themselves? I cannot tell. Pearls of water glisten on their backs. The head of one of them is only just beginning to show hints of the iridescent flash of emerald fire, a few stray baby feathers stick out at odd angles giving him a ruffled feel. The first hatchings of the year are now becoming almost indistinguishable from the full-grown adults. Swallows and martins arrow and spear, acrobatting, over the reed stands – the breath of their wings ruffling the water beneath them. On the hill above us, the grass has been cut. Kites fly low on an angle of wings.

This evening reminds me of a Haiku by the late 19th century Japanese poet, Shiki:

[READING]

The lethargy and lassitude that creeps over the body and hangs heavy and dusty over the fields and valleys of the last few days of heat is captured so beautifully by another haiku master, Taigi:

[READING]

Tonight, the moon is on the wane and now in its third quarter. There is something beguiling about the summer moon. It – or perhaps its light – has a different quality from that in winter. Perhaps the summer haze softens it and adds gold to its silver sheen.

[READING]

Wrote Hokushi in the late 17th century. Yes, it’s something I have done many times – though I more often find branches of oak and ash to frame the perfect light.

For the last couple of weeks, carp have been spawning. The water, particularly along the banksides and the shallows thrashed white. At night, they thud against the underside of the boat with hammering blows. In the afternoon, they doze, like aquatic cows in the sun-warmed, nicotine-brown shallows under the shade where the meadowsweet, dropwort and loosestrife hang low. Damsel flies dart electric above them. Yellow flags pods ripen and drop.

The cygnets continue to grow. They must be travelling further afield now, as they are not around quite so much. However, at least once a day, we are still treated to the military-style parade-like, grand entrance. Most times, Dad leading the line, six cygnets in a long regimental crocodile line, all followed by mum at the rear. The parents, heads erect, turning alternatively to the left and right – often synchronised with each other. They’re a spectacle that never fail to raise a smile – even if it is at the expense of someone’s sandal-clad, beak pecked, toes!

This weekend marks the anniversary of Maggie’s arrival on the boat. It must have been rather a whirlwind of a year for her as it is for us, but she has coped with it all admirably. We’re wondering if she can sense something – or maybe it is just the settling in – but she’s been a little awry recently. Pushing boundaries, but also becoming very clingy at times while at others wanting her own space. I seem to remember something similar happening with Penny, so we’re not too surprised. It can make it difficult to read her though. Just being a constant reassuring presence while she finds her feet, I think, is the key. We mustn’t also forget how much she has grown and matured during the time she has been here. She is a completely different dog to the one we met a year ago. It’s also nice as, at the moment, because of the constant movement of boats, there are lots of new dogs for her to play with which is wonderful. Here’s to many years more, Maggie!

[MUSIC]

CABIN CHAT

[MUSIC]

LIVING INSIDE THE SEASONS

It’s all come rather suddenly! This summer. After waiting so long, the thermometers shot up and left as reaching for our sunhats and usb air coolers! It didn’t last long, but long enough to remind us what real heat felt like. It was also quite a shock as literally the day before it came, I had dug out my jumper for the early morning walk. Nature’s Calendar, a book based on the 72 micro-seasons of Japan declare this week to be ‘Thunderbugs on Fizzing Elderflowers’ leading into ‘A Messy Riot.’ They’re both well named. Last week, I spotted a pair of swallows, a rush of arrow-flight, black and white and soft blur of dull red, needling over the hill and down towards the open stretch of canal. There’s plenty for them to eat after their long journey. Soft, muzzy gnat-veils hang and dance over the canal’s surface. Chaotic murmurations shoaling in lazy air of tiny dragons on breath-thin wings. The fish too appreciate these arial contortions, the mirrored water breaking in splashes that sends rings across the canal and into the thick new stands of reeds, where the moorhens hide.

The idea of adapting Japanese micro-seasons to British climate had been first done a few years earlier by conductor and writer Lev Parikian in his (2022) book Light Rain Sometimes Fall: A British year through Japan’s 72 seasons. Rather amazingly, Parikan names the five days when we recently experienced our first real taste of heat this year as ‘Insects Gather in the Heat’ while this latter part of the week falls under ‘Cool Winds sometimes Blow’! Parikan further goes onto note that the temperature has just dropped by ten degrees – just as it had for us!

However, all this is more than just a quirky appropriation of the calendar of some exotic or foreign culture in order to sell a few books. There is something interesting going on here, just as there is in the develop of the original calendar in Japan. Calendars can tell us a lot about how we, as a people, view not just time, but our perception of the world and what we mark as important. It also can act as a litmus paper to what things shape our lives.

There is a phrase in Beth Kempton’s book Wabi Sabi: Japanese wisdom for a perfectly imperfect life, that has struck me forcibly recently. Notwithstanding the ruinous effects of industrialisation and associated urbanisation of the past century which has led to the despoiling of landscapes celebrated in its art and literature, “[the Japanese, as a] people,” she wrote, “don’t just look at nature, they live inside it.”

On a technical level, one could argue that this could be said about anyone. We are after all, as humans, a product of nature and, therefore, despite all the walls we erect (physical and technological), we still live within nature and by definition nature is home to everyone and everything that is a product of this planet. But Beth Kempton is describing something much deeper here than simply stating the obvious.

What is it like, I wonder, to live not just alongside the seasons, but to live within them? To be part an ontological part of that shimmering dance of cycles within cycles as our home rotates its way in darkness around the sun? To vibrantly feel the spiralling complexity of the ebbs and falls as part of my journey and that my journey is part of the spiral of other journeys, human and non-human? How would that change me? What signals would I become more aware of as I watch the lengthen days, pause and then shorten, the rise and fall of temperature curves, the slow pendulum of the sun as it swings north and south along the skyline? Would I no longer just observe the colours of the towpath shift and change as petals bloom and fall, the thrust of grass peak and then die back, the changes in bird song, but, instead, be in some way be existentially part of them?

Kempton argues that there are a number of reasons behind this close connection between the Japanese, culturally, and their seasons. However, one of them is this continued use of such a detailed calendar that provides deep roots within this urbanised country and the soil. As Perikian notes, as well as ritualising and formalising the links between people and land, it also encourages a close observance of the world around them, creating points of familiarity and accord as well – and possibly more importantly – places of dissimilarity and change. They chart a familiar passage and throw into sharp relief those points of discord and change.

The ancient Japanese calendar has four main seasons (like those in the west) which are based around the solar calendar – of spring equinox, summer solstice, autumn equinox, and winter solstice. However, each of these main seasons is then divided into six. The names for these are either to mark the beginning on the main season (for example, Rikka – beginning of summer) or aspects of weather that characterise these periods – rainfall, frost, heat. The twenty-four subdivisions are then broken down into three further units to form seventy-two micro-seasons that last roughly five days each. Lev Parikian writes:

[READING]

I love the earthy rootedness of it all. This is a calendar with tap roots deep within the soil. Time marked by the opening and falling of blooms and leaf, the arrival and migration of birds. The recurring patterns of non-human lives. The last three weeks of Spring that run from April 20th to May 4th (collectively called Grain Rains) are known as: First Reeds Sprout, Last Frost – Rice Seedlings Grow, and Peonies Bloom. It is the winter season that draws out the more romantic. In October: Cold Dew: Wild geese return (October 8th - 12th), Chrysanthemums bloom (October 13th - 17th), Crickets chirp around the door (October 18th - 22nd). Rainbows hide (November 22nd - 26th), North wind blows the leaves from the trees (November 27th - December 1st).

There’s a deep poetry in these pragmatic pronouncements. You can read them as Zen Koans, almost haiku. There’s a lot invested in these spare words. If you want evidence of this melding of art and subsistence-style agriculture, lyricism and practicality, romanticism and weather-honed pragmatism, look to the beautiful collection of poetry from the Japanese anthology Kokinshū (completed around 905 AD) that was inspired by these 72 seasons and the journey they depict. I have an English translation by Larry Hammer titled Ice Melts in the Wind and published in 2018. The title is taken from another micro-season, ‘East Wind Melts the Ice’ (February 4th – 8th).

[READING]

There are also some surprising resonances with modern Western life here. The 9th century poet Sosei, writes:

[READING]

Yes, Sosei, I know that feeling all too well. Perhaps the distance between 21st century post-industrial Britain and 9 and 10th century Japan is not so great after all.

The one difference that I did note was the poignancy and sense of grief that infused so much of the waka (short-form) poems during the last weeks of Spring (Grain Rains). The long awaited and much celebrated showings of blossom, and in particular plum and then more latterly cherry fading, the petals falling in the winds. The reminder of transience, passing. The moving river that never stops, the letting go. Summer is greeted gladly, but also with a sense of melancholy, something I don’t really find in English poetry.

There’s an appreciation of beauty to though.

[READING]

(The cuckoo named here, however, is not the same as the European one.)

These are poems are not just abstract observations of nature and seasonal changes, but about human experience of them. Our reactions and responses (sometimes quirky) to the changes that chart the journey of the year.

Although we might have experienced them many, many times in the past, our capacity to still be entranced by how short the nights are and how long they stay light is clearly nothing new.

Although much later than the poems in Kokinshū, it reminds me of a Haiku poem by the late 19th century Japanese poet, Shiki

[READING]

Back to the Kokinshū

“Are you crying out

[READING]

The context here is also courtly love – and there is a subtly erotic interplay of images here and the night being too short to satisfy the lovers’ tryst (hence the cuckoo’s cry of dissatisfaction).

A little more whimsical is this poem. Its introductory subheading is “Written around dawn on a night the moon was lovely:”

[READING]

In these short, cryptic almost, word sketches, the experiences of past and present merge in moments of recognition.

I love this haiku by Buson an 18th century master of this type of verse, not so much for the image, but for the way I can intensely relate to the whole ghastly awkwardness of suddenly becoming aware of being observed and the crash of the human in a precious non-human encounter.

[READING]

I can feel my toes curl as I remember similar situations where a moment of almost transcendent connection splinters into a distinctly human one of suspicion and distrust. ‘What’s he doing in that field?’ ‘Why is that man hanging around the field gate?’ Yes, Buson, I’ve been there too.

But, perhaps, I will give Sosei the final word, that I think helps, at least me, to glimpse what it might be like to live inside the seasons –it’s a lovely summer poem and one that resonates down the thousand a more years to my ear and heart:

[READING]

SIGNING OFF

This is the narrowboat Erica signing off for the night and wishing you a very restful and peaceful night. Good night.