Wings of Angels (Cyril)

Over the last few weeks, we have watched our little swan family slowly begin the new phases in each of their lives. Whilst it can feel sad, it is also a celebration of the life of young Cyril who is now strong enough and equipped with enough skills to begin to make it in the adult world. It is also an endorsement of success for the young parents who, initially, encountered so many problems in nest building and egg laying.

Journal entry:

12th March, Saturday

“Last night I lay awake listening to the rain drum on the cabin roof.

Night-time is not a good time to think things through.

The shadows grow too dark and too large

The dressing gown hanging on the hook can too easily transform into a monster.

I could imagine the circles made by the rain on the dark waters beside me

And the hunched figures of ducks, heads tucked beneath wings one eye open.

And that, for me, made the difference.”

Episode Information:

Photograph taken by Jeremy of Cyril (forefront) and parents in flight.

Cyril

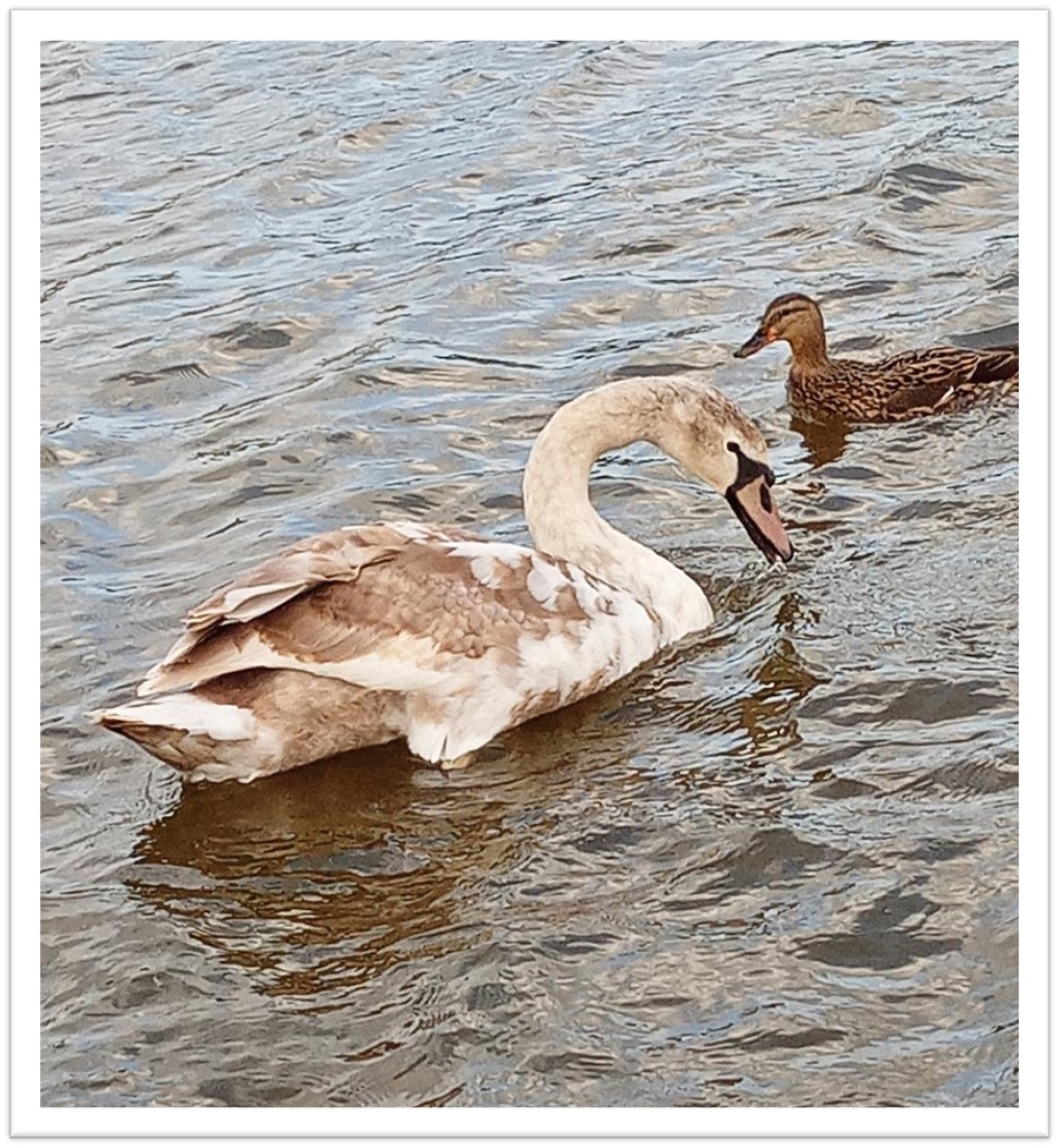

Brown outer plumage and bluish tinge to the beak provide visible signals to adult male swans that he is not a threat

Cyril feeding

Cyril brown juvenile feathers still very visible

In this episode I refer to the following books:

Malcolm Schuyl’s The Swan: A natural history published (2012) by Merlin Unwin Books. This is probably the most authoritative book on the subject and is accompanied by some wonderful photography.

Simon Barns quirky but indispensable A Bad Birdwatcher’s Companion (2005) published by Short Books. The audio book is excellent, entertaining, lavishly produced and offering samples of each bird call too!

More information about Nighttime on Still Waters

You can find more information and photographs about the podcasts and life aboard the Erica on our website at noswpod.com. It will also allow you to become more a part of the podcast and you can leave comments, offer suggestions, and reviews. You can even, if you want, leave me a voice mail by clicking on the microphone icon.

General Details

In the intro and the outro, Saint-Saen's The Swan is performed by Karr and Bernstein (1961) and available on CC at archive.org.

Two-stroke narrowboat engine recorded by 'James2nd' on the River Weaver, Cheshire. Uploaded to Freesound.org on 23rd June 2018. Creative Commons Licence.

Piano and keyboard interludes composed and performed by Helen Ingram.

All other audio recorded on site.

Contact

For pictures of Erica and images related to the podcasts or to contact me, follow me on:

- Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/noswpod

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nighttimeonstillwaters/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/NoswPod

I would love to hear from you. You can email me at nighttimeonstillwaters@gmail.com or drop me a line by going to the nowspod website and using either the contact form or, if you prefer, record your message using the voicemail facility by clicking on the microphone icon.

It is a beautiful picture. Three strong figures, unglazed white, high in a sky of Wedgewood blue. The leading figure, slightly smaller, arrow sharp. Behind, two parents, slightly closer to each other matching broad graceful wingbeat for wingbeat. The sun catches the primary flight feathers, and darker wing lining feathers and coverts. They look like depictions of angel’s wings.

Our pair of adult swans taking flight with their youngster Cyril.

It’s a picture full of poignancy too. Jeremy the photographer, described it as if the parents were giving Cyril a flying lesson. It’s the last time I have seen them fly together. Perhaps, this will be the last picture of them together as a family. I saw them together a day or so later, but all three were on guard – not aggressive, but alert. Bristling. Wings arced, although not fully busking. Messages were being sent and received. Cyril and his parents keeping an uneasy distance. Cyril’s cygnet’s peeps and whistles silent. Since then, the parents have regularly been back, but without Cyril.

I discovered him this morning as the dawn was softening the sky, on his own, in the middle of little cow pond. Head tucked right under his wing. If he sensed our presence, he did not show it. He made no movement. It's a good spot for him to sleep. Secluded, the pond is large enough to deter an opportunistic attack. There was no sign of his parents. I was glad.

The time had come for Cyril and his parents to embark on the next stages of their lives.

Did they know this as they were flying under cornflower skies their wings lit like angels? Even while they were moving apart, pushing Cyril away, did they feel that parental tension? Keeping an eye on him, teaching him the skills that he would need, making sure he could read the currents of the air through his pinions whilst simultaneously saying, now is the time to go? Is that what is happening in that photograph, the confliction of keeping safe and letting go? Two adults renewing their bond as nesting ad breeding season begins, but also checking on their offspring. Giving him every chance? Or are they simply shepherding him away? We’ll never know.

Earlier in the week, Penny and I were beside the remnants of their nest - it was always more of a heap, a land-borne raft of reeds and grasses. It is still here, among the reed die-back – a few shards of shell still remain – perhaps one part of the egg that contained the strong life of Cyril.

The parents were young, new to parenthood. So many attempts to build a nest. Eggs laid and then abandoned, until one day in mid June, 5 cygnets were born. Four were sadly taken one night in July, but Cyril survived and, if you have listened to earlier podcasts, you will already know of his adventures, getting lost, being rescued, Cyril has grown.

The parents have done well. They had no handbook, no instruction manual. They have tried, experimented, got it wrong, persevered. Cyril is a credit to them. And now it is time to leave.

Malcom Schuyl’s magnificent book The Swan: A natural history explains that parents and offspring “will stay together as a family unit until the spring, when the urge to breed once again takes over the adult birds and the young are quite literally chased away.”

Schuyl goes on to state, “Once they leave their parents, young swans usually join up with other adolescent birds until they become old enough to find a mate and breed themselves. Most groups of swans seen on rivers and lakes comprise such birds, together with non-breeding adults.”

Simon Barnes, in what to my mind is the best guide for any one beginning birdwatching, The Bad Birdwatchers Companion, points out that there is a very good reason why young swans hold on to their juvenile plumage - at this most dangerous time in their life, it signals to more mature swans that they are no threat.

And it's true that juveniles who have refused to leave for one reason or another, have been killed. Usually, at this point, talk turns to the cruelty or harshness of nature as if we were in some way separate from it, as if we were no longer are a part of it having transcended above it, and yet can hold it accountable.

But there is nothing strange about this process. The parting of Cyril and his parents is something nearly every one of us has experienced - that conflicted, messily emotionally confused adolescent period of growing up. Perhaps some have experienced it from both sides - parent and child. But what Cyril has experienced is no more than that natural process of growing up. Yes, Schuyl is right to say that to the observer it can be disturbing, watching a youngster be rejected by their parent. Perhaps, because it awakens in us those conflicted feelings of empathy, pity, anger. Re-stirring those days when there is an ever-growing awareness that the very things that made me feel safe, loved, protected, and which kept me close to the family home, now began to evoke such strong opposite emotions.

I can remember my adolescence. I took it hard. Nowhere near as hard as many have, but for my limited worldliness, pretty hard. Spending lots of time locking myself away in my bedroom, looking out of the window. During the winter, playing records on the old gramophone player with the Aladdin bowl heater roaring away and turning my legs red and blotchy, the room smelling hot with paraffin and scorched linen. In the summer evenings, sitting on the window sill with the cherry blossom just within reach, losing myself in the amber glow of the street lamp on Coniston Road and the great long cliff of roof tiles – letting the scents and sounds of the neighbourhood rise up to me like a Janis Ian song, and imagining the lives happening in all the houses and gardens up and down the road. The roads behind, so familiar and yet so unknown, so that their names, Coniston Road, Osbourne Avenue, Belham Road, Havelock Road, Whitlers Drive, sang to me like undiscovered countries. And, for me, in many ways, they were. Sitting there at the table by the window, two fingers stabbing at the old typewriter keyboard tapping out terrible prose and poetry. So much stuff filled my head. So many words, but I had nothing to say. There were days at that time when I felt so alive it was as if I wore no skin at all, just bare nerves jangling with the unfathomable, almost indescribable beauty and vividness of everything I encountered. At times, it was almost unbearable and I had no words to convey it. And so I just typed and typed and typed. There are nights when I am still there, at that overloaded window sill in front of the cherry tree, sitting at the typewriter, typing, typing, typing – desperately trying to find something to say.

Much later in life when we were talking about adolescence and growing up, I mentioned to Mum about my rebellious period, when I'd cut myself off. I felt guilty and sad that, however I was feeling, it must have felt hurtful. She replied 'Oh, did you dear? We didn't notice!'

How did Cyril and his parents process these changes and shifts in their relationships? Did they understand it any better than I did? What was once protective, began to feel restrictive. What once drew me began to repel me. Did the poles in their lives change as they did in mine (and every other adolescent)? All I knew was that what felt familiar comforting, reassuring, began to feel odd. Off-key. Wrong. As much as I wanted to stay, I also had a peculiar and unsettling feel that it was time to leave; to break free and fly the nest. I was fortunate as Mum and Dad gave me space so the transition then into adulthood was fairly painless.

That time for Cyril has also come. The world perhaps feeling a little larger, more uncompromising, perhaps a little less safe, a bit less secure and feeling more unpredictable. Feelings that many of us have been experiencing recently.

After, nearly two weeks, on Wednesday, he reappeared. His brown mottled plumage softening out to white, giving him a slightly unkempt, blotchy, muddy, appearance. But I am mindful of Simon Barne's comment about the youthful brown offers protection, and so I am glad that even in its diminishing, with his bluish beak, it is still visible. I had been keeping my eye open for him as earlier in the morning, Karl had posted on Whatsapp that he was in the vicinity.

All winter we'd not been feeding the ducks because of avian flu. The mildness of the season also meant that there has been plenty of food around and it is good not to let birds get too dependent - change their habits, even battle over new territories - on the capricious whims of human generosity. Nevertheless, for old times' sake I rushed back down into the stern to get the little bucket of duck food. He had already seen me and was, even then, gliding over, the smooth, unhurried, alternate-footed, doggy paddle. His head cocked to one-side, short glances to left and right.

As always when food is around, ducks shuffled off their invisibility cloaks, emerging close to the boat from out of nowhere. It was good meeting him. Being in contact. Crouched on the stern, looking into those beetle-black glistening eyes. The assured movements, the unhurried nuzzling and sifting of water. There is no place for pity or sadness or even loss in them - if he feels different, if he feels as if the world is in some-way changed, and he must do, his glances up and down are not for the companionship of his parents, but to distance himself from them. However he processes that and whatever chemical responses that churns in his body and brain, it must feel right, the way things are as they should be.His world, as our world, is always in the state of change. The shifts in the light as a cloud passes below the sun, the flow of warmth over a frosty meadow as the sun rises. The play and dance of air currents, thrilling and eddying over copse and hillsides that he is learning to master on his still juvenile wings. It's just a fraction of a second eye contact, but it is clear and unambiguous. In the directness of that fleeting moment, I am, of course, really just seeing within the blackness of those eyes a reflection of me. Me through the eyes of another, none human, more than human. One who experiences the world in ways that I cannot. Who feels the water, its movements, the ebbs and currents, the soup of nourishment that lazily folds and unfolds above rich muds the canal bed. Who touches the winds in ways I cannot and knows a significance to their movements that is hidden from me. Who encounters the rush of the same hormones in his body that I feel in mine, but perhaps experiences them in other ways?

For a while it feels as if I am part of a larger, richer world, in which the Berlin Walls that segregates species, that emphasises difference and locks them into categories according to physiognomy and utility, dissolve. That I am touching the world as we lived it, before the Great Disconnect. Before we, as a species, took the decisions to alienate ourselves from our home and those we share it with. To withdraw into the smallness of a small world and the penury that this brings. Together, Cyril and I float on the same waters and feel the same easterly wind. We share the same world and both live by our senses, using whatever we can to process and understand them. Brothers and strangers, kin and alien. The connection, albeit fleeting and nebulous, of two beings who experience and share the same world. The 'we' of Buber's I-Thou. Never now I-it

Not in a way that naively tries to reduce a swan of his distinctive swanishness, the enforcing of a human mould - a sentimentalised bird-human hybrid - as if we humans are only capable of finding community and a sense of connection and significance with others like us. Cyril and I may feel our shared space within the world in very different ways, but we also share so much in that feeling. Winds veer and back, rains lash the water until it hisses and bubbles and then goes. The once comforting shadow of a parent no longer feels the same and new waters beckon and call.

For things to remain as they have done, unchanged, without growth, without development, would have been to impose something unnatural, something alien, something that would have betrayed the swan in him and his parents.

I go back below to put the food pot back in its place. I peek out of the porthole by the stove. A quick little wag of the tail, a dip of the beak to drink some water, and off he pushes leaving behind a chaos of ducks and a bobbing widgeon.